Studying the genetic structures of various living organisms can yield very important information about how the brain develops at a genetic level. There is astonishing diversity in the nervous systems of animals, and the variation between species is remarkable. From the basic, distributed nervous systems of jellyfish and sea anemones to the centralized neural networks of squid and octopuses to the complex brain structures at the terminal end of the neural tube in vertebrates, the variation across species is humbling.

Often when talking about diversity of nervous systems, people may claim that “more advanced” species like humans are the result of an increasingly centralized nervous system that was produced through evolution. This claim of advancement through evolution is a common, but misleading, one. It suggests that evolution always moves in one direction: the advancement of species by increasing complexity. In fact, genetic information of living things is in a constant state of flux which produces a variations within species that than evolve. Evolution, therefore, can be defined as the process in which an environment selectively promotes living organisms carrying the genetic information required for a specific body structure or way of life. Hence evolution may selectively enable body structures that are more enhanced and complicated, but it may just as easily enable species that have abandon complex adaptations in favour of simplification. Brains, too, have evolved in the same way. While the brains of some species, including humans, developed to allow them to thrive, others have abandoned their brains because they are no longer necessary.

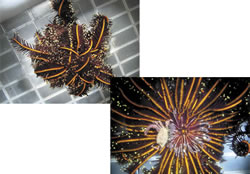

For example, the ascidian, or sea squirt, lives in shallow coastal waters and which is a staple food in certain regions, has a vertebrate-like neural structure with a neural tube and notochord in its larval stage. As the larvae becomes an adult, however, these features disappear until only very basic ganglions remain. In evolutionary terms this animal is a “winner” because it develops a very simplified neural system better adapted to a stationary life in seawater. The feather star, Comatulida, is part of the echinoderm phylum with starfish, sea urchin and sea cucumbers (see Photo). The fossil record and other data suggests that the Comatulida is an older species that may be more closely related to extinct echinoderms than to present day echinoderms. Yet, while starfish, sea urchins and sea cucumber may have appeared more recently, they have a simpler nervous system than the feather star.

The most extreme example of an species that has completely abandoned its nervous system is the Dicyemida. This tiny animal of about 50 cells is a parasite that lives in the kidneys octopuses and squid. Although it has no nervous system now, a genetic comparison has shown that it may have “evolved” invertebrates that had some type of nervous system. Apparently there are environments where having a brain or nervous system is unnecessary. The existence of these animals suggests that developing a brain to enhance “intelligence” is not necessarily the most effective means for survival.

Our laboratory seeks to understand the human brain, which is a very attractive research subject that is also very “risky” in terms of its application. The impact of the human brain on humanity’s ability to drastically alter the global environment has driven other species to the point of extinction. This brain is also capable of exerting a such a negative impact on its environment that humans pose a threat to their own prosperity. It was a group of human brains that developed of weapons of mass destruction (WMDs). It is also true that the present stage of human prosperity was also possible thanks to the brain. In the long run, however, evolutionary success will be determined by what species survives longer: humans with their complex brains or the brainless Dicyemida.